|

The newest U.S. space telescope has found what could be the youngest planet ever observed, less than one million years old. Astronomers are amazed at the apparent speed with which it formed, suggesting that solar systems like ours could come together quickly, and be more common than thought. The telescope has even detected life-creating compounds in the same region.

The story of how we and the ground beneath our feet evolved from space dust is beginning to unfold with three new findings from the U.S. Spitzer Space Telescope. The observatory has witnessed star and planet evolution in other parts of our Milky Way galaxy, and the combined discoveries support the belief that there may be life on other planets outside our solar system.

One finding came during an observation of a star nursery nearly 14,000 light years from Earth. Spitzer observed more 300 stars being born with planet-forming disks of dust swirling around two of them, the same dust from which the stars are forming. Preliminary evidence suggests all the stars have such disks.

"This is beyond our wildest dreams of anyone's expectation, I think, of the number of star formations in a single region," he said.

This is University of Wisconsin astronomer Ed Churchwell. "Why is that important? Star formation is kind of like the life-blood of a galaxy. If it weren't for that, galaxies would very quickly burn out and not be visible," he said.

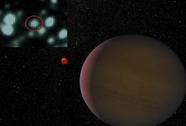

Spitzer also surveyed another group of young stars in the Milky Way, and found intriguing evidence that one of them, just a million years old, may have a planet even younger. The star's age is measured by its bluish color. Mature stars are red, orange or yellow. The planet orbiting it would be the youngest ever observed. By comparison, Earth and the solar system are four-and-a-half-billion years old. Spitzer saw the baby planet within a hole in the star's dusty disk. This might indicate the planet formed from the dust.

If so, Carnegie Institution astronomer Alan Boss says this explains how it could gather so quickly. Mr. Boss, who did not participate in the observations, says the previous view of planet formation was that they accumulate when big space rocks or lumps of ice crash into each other. But he says that process takes millions of years, while accretion of dust in a star's disk could occur blazingly fast by comparison, and might be the more frequent method of making planets.

"The gaseous portion of the disk can actually pull itself together rather quickly on a timescale, perhaps, of only a thousand years, have its dust grains settle down inside to form a core, and, more or less, become a complete planet on a time scale that's about a thousand times faster than the leading contender," he said.

A third Spitzer observation could explain how life got started on Earth, and why it might be common elsewhere. It found ice particles with organic compounds within discs circling five young stars in the constellation Taurus, relatively close to us at 420 light years away. Dan Watson, an astronomer at the University of Rochester in New York state, says this may explain the origin of icy bodies like comets and asteroids.

"Remember, the asteroids and comets in our solar system are supposed to have brought the water and other life-building materials that we have to Earth and filled up the oceans," he said.

The Spitzer telescope, which was launched last August, can discern these phenomena, because it has infrared detectors of unprecedented sensitivity. They allow it to see things shrouded in dust, which does not block infrared radiation.

For the Carnegie Institution's Alan Boss, the observatory's trio of new findings have profound implications about the possible prevalence of planetary systems like ours.

"These three Spitzer results, of the [young] planet, the ices, and the regions of high mass star formation, all tie together in a very nice cohesive picture that says that it may very well be that solar systems like our own are probably not rare in the galaxy. They may actually be a very common case," said Mr. Boss.

* * *

You are welcome to print and circulate all articles published on Clearharmony and their content, but please quote the source.

more ...

more ...