In ancient times, it was extremely difficult for people to produce purple dye from nature. That is why cloth dyed purple was extremely rare and expensive in ancient times. Duke Huan of the Qi State in the Spring and Autumn Period (722 – 481 B.C.) became at once notorious because he was partial to purple outfits and, thus, caused the merchants to increase the price of the already expensive purple fabrics tenfold.

The ancient Greeks and Romans were able to make an alizarin purple dye from the root of the Eurasian madder, and they used the alizarin dye for dyeing fabrics and for painting. The only drawback was that it was not true purple but a colour closer to burgundy. The ancient Greeks, Indians and Persians solved this problem by mixing red and blue dyes. When scientists were researching candidate materials for superconductors during the 1980’s, they accidentally produced a purple dye – BaCuSi2O6, also known as “Han Purple.” BaCuSi2O6 has never been discovered in nature, and it is difficult to produce BaCuSi2O6 even with modern technology.

Therefore, it came as a complete shock when experts from an artifact preservation bureau in Bavaria, Germany, who had participated in research on the technology used to preserve the colour of painted wood and clay figures of soldiers and horses buried with the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty (259 – 210 B.C.) in China, made the following announcement when they attended the 1997 Artifact Preservation Seminar in Taiwan: “Our research has concluded that Han Blue (BaCuSi4O) and Han Purple (BaCuSi2O6) were commonly used dyes in the Caves of Dunhuang in China’s Gansu Province (a treasure house of Buddhist scriptures, paintings and statues) and on painted wood and clay figures of soldiers and horses buried with the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty.”

The German artifact preservation experts’ discovery created a lot of excitement and raised many new questions in the field of archaeology: “How did the ancient Chinese people produce BaCuSi4O and BaCuSi2O6? Transportation limited information exchange in ancient times. Thus, dyes were prepared from materials found in nature in each region. Moreover, today’s people were not able to produce BaCuSi2O6 with modern technology until just a couple decades ago. How could Chinese people possibly have the technology to produce BaCuSi2O6 in 200 B.C.?”

|

| Purple dye on this painted clay soldier buried with the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty is BaCuSi2O6, also known as Han Purple |

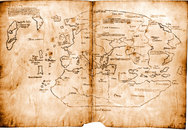

Another discovery of modern dye was found in an ancient artifact found in the United States. It is the controversial Vinland Map. The Vinland Map is a Latin map dated 1434. It is currently being kept at Yale University. Most scholars think it is real, but many regard it as a forgery because of the presence of anatase, a particular form of titanium dioxide, in the ink. In a paper published in the August 2002 issue of the journal Radiocarbon, scientists conclude that the Vinland Map parchment dates to approximately 1434 A.D., or nearly 60 years before Christopher Columbus set foot in the West Indies.[1]

The Vinland Map was first discovered in 1957 in a bookstore in Geneva, Switzerland. It is a sheepskin parchment that measures 15.76 inches long and 11.03 inches wide. No one knows to whom it belonged to previously. On the map, Vinland appears to be located to the west of Europe. The text on the map reads, in part, “By God’s will, after a long voyage from the island of Greenland to the south toward the most distant remaining parts of the western ocean sea, sailing southward amidst the ice, the companions Bjarni and Leif Erikson discovered a new land, extremely fertile and even having vines, ... which island they named Vinland.”

|

| This controversial parchment, called the Vinland Map, is housed in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library |

Beginning in 1995, Harbottle, along with Douglas J. Donahue of the University of Arizona, and Jacqueline S. Olin of the Smithsonian Centre for Materials Research and Education, undertook a detailed scientific study of the parchment. Using the National Science Foundation-University of Arizona’s Accelerator Mass Spectrometer, the scientists determined a precise date of 1434 A.D. plus or minus eleven years. The unusually high precision of the date was possible because the parchment’s date fell in a very favourable region of the carbon-14 dating calibration curve. This announcement has confirmed that the Vinland Map dates to the 15th century. It follows that Columbus may have already known about the Vinland Map prior to his discovery of North America.

Since the discovery of the Vinland Map, many scientists have claimed it to be a forgery. The biggest argument has been: “The ink on the map can only be made with modern synthetic technology. Europeans did not have such technology in the medieval ages.” Robin Clark, D. Sc., Sir William Ramsay Professor of Chemistry at University College, London, U.K., and doctoral candidate Katherine Brown, used Roman microprobe spectroscopy to identify the chemical components in the inks on the Vinland Map. They discovered that the ink contained anatase (TiO2), the least common form of titanium dioxide found in nature. Some scientists have thus concluded that the map must be of 20th-century origin because anatase could not be synthesised until around 1923. [2]

To vindicate the Vinland Map, Jacqueline Olin simulated medieval iron gall ink that resembled the ink found on the map. Her simulated iron gall ink does contain anatase (TiO2) [3]. However, Dr. Kenneth M. Towe, a geologist in the Department of Paleobiology, The Smithsonian Institution, argued in his 2004 article in Analytical Chemistry, “Medieval iron gall inks are rich in iron.” However, analytical evidence showed that there is a very low percentage of iron in the ink found on the map. [4]

Olin’s response was that the iron may have disappeared because of the deterioration of the ink and she suggested further research on different kinds of inks containing titanium. She further pointed out that the ink found on the map contains copper, zinc, aluminium, and gold, which is similar to many medieval inks. Nevertheless, Robin J. H. Clark, Christopher Ingold Laboratories, University College London, quickly dismissed her arguments: “Unfortunately her article is based on speculation, lacks logic, and lacks either new information or new insight on the ink, consisting merely of a rewriting of her earlier publications. Its publication has provided the scientific and popular press with fuel with which to fire further, entirely unjustified, controversy on this subject.” [5]

There are two main reasons for the heated debate over the authenticity of the Vinland Map. First, it is a general assumption for chemists that ancient technology must have been far less advanced than modern technology. It follows that, when a relic contains a compound made by technology invented in modern times, modern scientists are likely to hold fast to their assumption and claim it to be a forgery. Second, for a historian to acknowledge the authenticity of the Vinland Map is to prepare to rewrite the history that Columbus was the first to discover North America. This is a change which modern orthodox historians are not yet willing to accept.

In comparison to the highly controversial Vinland Map, the Chinese Han Blue and Han Purple dyes are less controversial. Because samples of dyes were taken directly from wooden and clay figures of soldiers and horses buried in the tomb of the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty, no one can question the authenticity of the dyes. If samples of the dyes had been collected from the antique collection of a Chinese antique dealer in Beijing, many people whose minds are tightly delimited within their own boundaries, would have jumped to their feet and argued that the ancient Han Purple dye has to be a modern forgery.

Many ancient relics and historical records have been discovered. Many artifacts found in ancient tombs or ancient inventions recorded in historical records were made with technology on a par with or surpassing modern technology. The Han Purple dye found on wooden and clay figures of soldiers and horses buried in ancient tombs is one genuine case that modern scientists cannot deny. Scientists once claimed the prehistoric frescoes in the caves of Altamira were modern forgeries because the earth pigments found on those frescoes were too exquisite for scientists to believe that they were prehistoric pigments. Scientists eventually proved the Altamira cave frescoes to be authentic. This is a lesson that, if we can free ourselves from the many preconceived notions and existing frameworks of science and be truly objective in our scientific analysis, humankind might develop a more accurate and profound understanding of its own history and culture.

Bibliography:

[1] Donahue, D. J.; Olin, J. S.; Harbottle, G. Determination of the Radiocarbon Age of Parchment of the Vinland Map (2002) Radiocarbon, 44, 45-52.

[2] Brown, K. L.; Clark, R. J. H. Analysis of Pigmentary Materials on the Vinland Map and Tartar Relation by Raman Microprobe Spectroscopy (2002) Analytical Chemistry, 74, 3658-3661.

[3] Olin, J. S. Evidence That the Vinland Map Is Medieval (2003) Analytical Chemistry, 75, 6745-6747.

[4] Towe, K. M. The Vinland Map Ink Is NOT Medieval (2004) Analytical Chemistry, 76, 863-865.

[5] Clark, R. J. H. The Vinland Map- Still a 20th Century Forgery (2004) Analytical Chemistry, 76, 2423.

* * *

You are welcome to print and circulate all articles published on Clearharmony and their content, but please quote the source.

more ...

more ...